There is much one can infer from these characteristics—from the signs telling stories about how they were made.

Most signs require thoughtful deliberation to communicate effectively: how to articulate their message, how to compose it, when and how to maintain versatility, etc. But it’s vernacular signs that inscribe these decisions onto the canvas itself, revealing the unique challenges of each sign and how their signmakers chose to address them.

Because vernacular signmakers typically work with their hands, they don’t have the luxury of using “Command+Z” nor can they resize elements once they realize they’re too big or too small. Instead, they must respond to these issues on the fly. Much of how they respond can be inferred by paying attention to the inscriptions on the sign, such as when the word “parking” or “tacos” proves to be too long and the signmaker must figure out where to place the remaining letters. In addition, vernacular signs can also reveal the more practical aspects of signmaking, such as when the hours of operation or price of cigarettes change (but the change isn’t significant enough to justify the creation of a whole new sign).

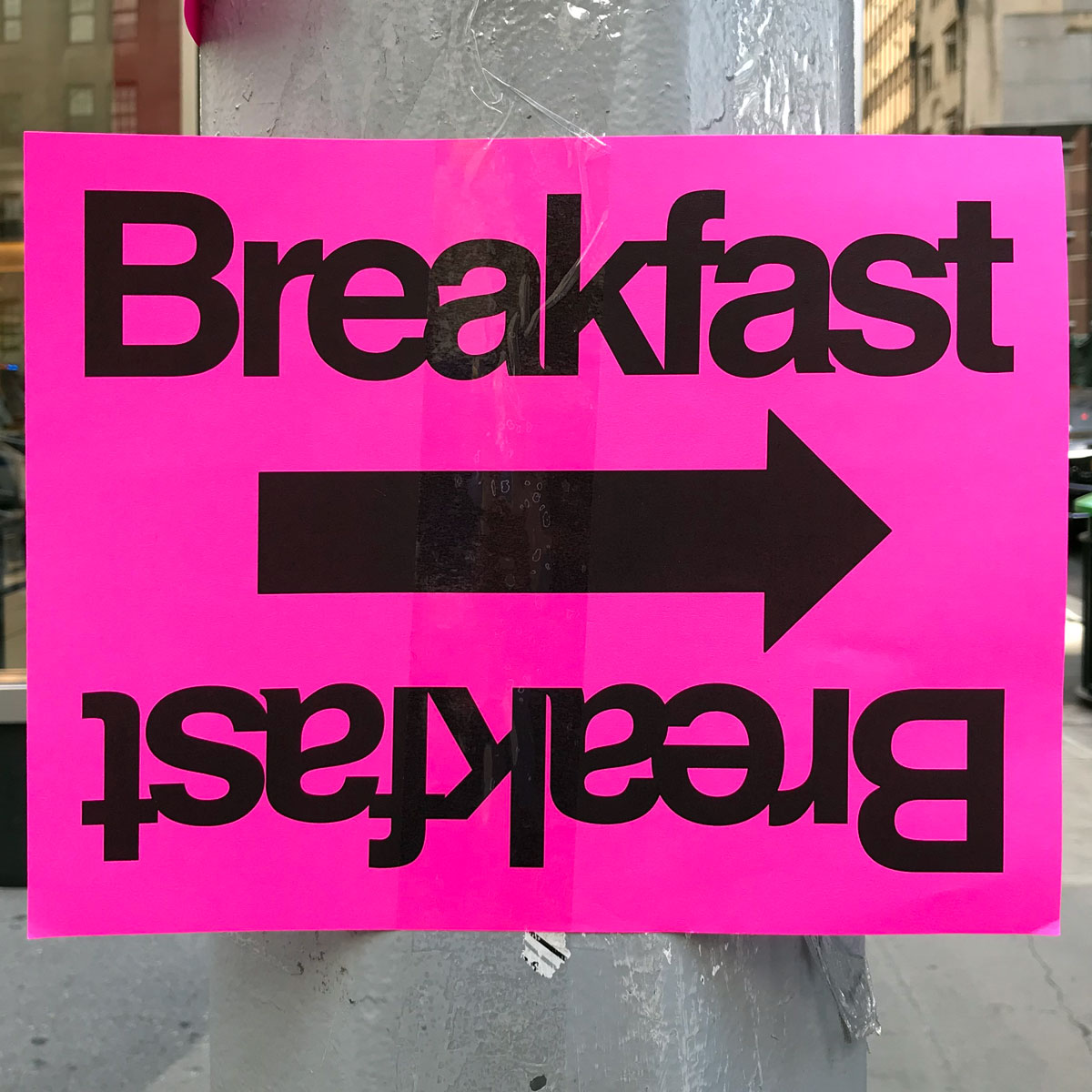

When these signmakers do have the luxury of designing with software, such as with the pink “breakfast” sign, what can be inferred is different but still rich. This sign reveals not only how volatile the location of breakfast for these events actually is, but how the signmaker must respond to this volatility. Instead of printing different signs with arrows facing different directions, why not print one sign that can be spun around?